My adopted son told us something that will forever break my heart

All about how What Your Bones Know may well be the Primal Wound

“But I think it is my fault. My parents wouldn’t have given me up if I wasn’t bad.”

Oof. I had felt so good about the conversation. I had what I thought was a bullet-proof line in my back pocket for difficult conversations with our adopted kids. It had worked before.

This time, I was talking to one of the kids about conflict with a classmate. We repeated our standard explanation: “When you were a baby, you didn’t have safe adults to help you so you felt like you had to fight to keep yourself safe. Now, sometimes your body still decides to fight when you’re having big feelings.” And then the typical call to action: “It’s not your fault that it’s harder to make good choices but it is your responsibility, with our help, to learn how to be able to make them.”

But that response. That heartbreaking response. How can an innocent, sweet, perfect little boy be carrying that belief around inside him? No wonder his feelings are so intense. No wonder that fight-or-flight reaction lies so close to the surface.

He kept going: “I think I must have done something wrong or they would have kept me.”

Can you picture an infant in their first month of life? It feels impossible to believe but even as kids are taken away from their parents and put to stay with foster parents, the seeds of the belief that there’s something wrong with them are being scattered and starting to take root. “There must be something wrong with me.” “I did something wrong.” “It’s my fault.” What could be less true? But the feeling they carry inside is so real.

We said something in response, of course. Some empty words. Pebbles that feebly scatter when thrown against the granite mountain of hurt he carries inside. I think what probably made more of an impact than anything else was my tears. Kids take notice when grown-ups cry. My voice broke and tears came again and again as I tried to say something, anything, that would take his pain away.

Someday we’ll invite him to read The Primal Wound. It’s written by an adoptive mom who is seeking to understand the struggles of her daughter, adopted at birth. This book receives some criticism because it is written by an adoptive parent and not an adoptee, but it also has currency in the adoption world and is a widely recommended resource. Although the tide seems to be changing, it’s historically been very difficult for the public at large to acknowledge the tragedy and loss that are inherent to adoption. Especially when kids are adopted at birth, the common perspective seems to have been that there’s essentially no difference between kids who were relinquished for adoption and those who weren’t. Verrier challenges this belief.

As an adoptive parent to a child who struggled with her mental health, Verrier began asking, “What predisposes adopted children to this vulnerability?”1 The answer, she believes, lies in a “primal wound” which is physical, emotional, psychological and spiritual. This wound was “caused by the separation of the child from his biological mother, the connection to whom seems mystical, mysterious, spiritual and everlasting.” For adoptees, this primal wound is so profoundly painful that they, from infancy or toddlerhood, may throw up obstacles to close relationship with their adoptive parents. For the adoptee with this primal wound, “allowing herself to love and be loved was too dangerous. She couldn’t trust that she would not again be abandoned.” Whether they were adopted at birth or later, Verrier asserts, “adopted children experience themselves as unwanted [and] are unable to trust the adoptive relationship.” She cites the experience of clinicians working with adoptees who observe that they all have “essentially the same issues, [centering around] separation and loss, trust, rejection, guilt and shame, identity, intimacy, loyalty and mastery or power and control.” All caused by that early, often not-remembered, wound of separation from the biological mother who constituted the infant’s entire world and, in fact, their entire sense of self.

Perhaps we’ll also encourage him to read What My Bones Know by Stephanie Foo. It’s a good read. She’s able to communicate complex, tragic information in a highly-readable way. She knows just when to inject some humor or a meta-level nod to the readers acknowledging the uncomfortable darkness of her story while also providing a direct and challenging recounting of her life history and her family’s generational traumas. It’s no surprise that Foo is a talented story-teller; she’s been a successful journalist and podcaster since high school. In the book she explains how using workaholism as a way to numb her pain allowed her to earn a spot on the staff of This American Life, producing a number of well-regarded episodes of their weekly radio show.

What My Bones Know is a memoir of the author’s grappling with how to understand and find some level of healing from a childhood filled with physical and verbal abuse. As an adult, Foo realizes that even her high-achieving life that she shares with a loving, supportive boyfriend and a good group of friends has not actually managed to change the nature of her internal experience. Namely, she feels desperately and perpetually shitty inside. When she finally gets a diagnosis of C-PTSD, she’s able to give that feeling of generalized shittiness a name and an explanation. But none of that, not the self-understanding, not the diagnostic label, not the objectively not-shitty nature of her adult life can make her stop feeling like shit inside.

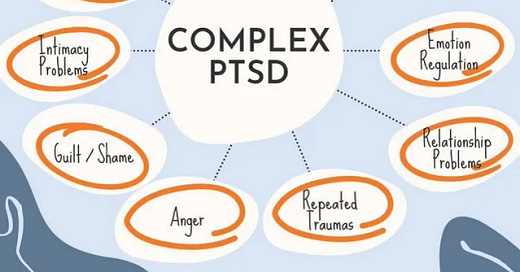

That chronic shitty feeling is in fact one of the symptoms that distinguishes C-PTSD from PTSD. The chronic, environmentally pervasive stressors that results in C-PTSD (as opposed to the episodic or situation specific stressors traditionally understood to result in PTSD), affect the mind and body in predictable but often not-easily-observable ways. An outside observer cannot always perceive the internal struggle to regulate mood and oppressive patterns of disordered thinking that someone with C-PTSD experiences. For the sufferer, it may be difficult to adequately communicate these realities (especially if you’re a child), because this is just the water they swim in. They may not know how different their inner world is from other people’s. Hard to spot though they may be, these symptoms of emotional regulation problems, issues with identity and sense of self, and problems in relationship are as typical of C-PTSD as little red itchy spots on the body are to chicken pox.

In both books, the authors confront the hard realities that there are some early life experiences that can fundamentally and permanently change our sense of self. Children who go through really hard things when they’re young inevitably attempt to somehow make sense of what they’re experiencing. In a heart-breaking dynamic that heaps pain upon pain, the common conclusion is: “There must be something wrong with me.” Source after source attests to how kids who experience abuse and neglect2 will come to believe with deep inner conviction that they are somehow responsible for what’s been done to them. They’ll believe “I’m bad,” “I’m worthless,” “I’m not good enough,” “I’m defective.” These deep feelings of guilt and shame will cause them to feel “fundamentally flawed or as though they’re different from everyone else.” These lies will be “what their bones know.” They will believe these things to be true with as little doubt as they believe the sun will rise in the morning.3 This primal wound cuts deep, down to the bone, and is very difficult to heal.

As an adoptive parent, the work I’m engaged in is to be a companion in my kids’ lifelong journeys towards healing. I want desperately for “what their bones know” to be that they are lovable and loved. It’s what any of us wants for our children. But, acknowledging that this primal wound might never fully heal, I also want them to know that it’s okay for them not to be okay. We will be here with them every step of the journey, will love them in their hurt and will make space for their pain.

Verrier notes in the book that adopted children are disproportionately likely to experience difficulties in shool, in relationships, and in their mental health than non-adopted peers. She states: “Adoptees comprise 2-3% of the population of this country [but] they represent 30-40% of the individuals found in residential treatment centers, juvenile hall, and special schools.”

(as well as kids who experience the early life trauma of parental separation through adoption)

But having said that, I do want to acknowledge that not every adoptee will experience that sense of primal wound and self-blame that I am discussing here. From my reading and research, these are common experiences but not universal.

Good information to know but hard to hear, especially when it pertains to one's own children or grandchildren. It makes sense and the stats about problems adoptive children have to deal with clearly demonstrate the accuracy of what you wrote. Knowing about this wounded soul at least gives parents insight into what they can do to help their children.

An amazing read! Brought tears to my eyes. I am going to read the books you are suggesting here.