How I learned to stop judging and love my child's parents

What Debs, Demon, and a 4-level chart teach us about how to show up for people

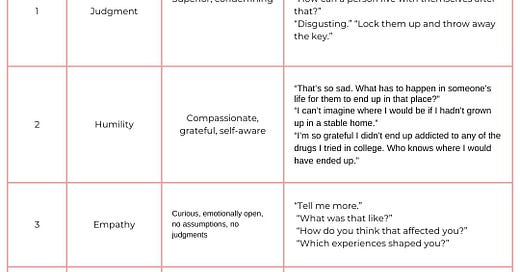

I can explain my attitude towards my kids’ birth parents as a four-level system. Whether you have adopted kids or not, it’s a paradigm that you can use too. It’s helpful for reflecting on our own thoughts about any sort of person we are tempted to judge from afar or judge harshly.1 There’s not a strict linear progression in this system: we’re all at different levels at different times or towards different people. We can move between the levels in response to events, ideologies, personal experiences, and philosophical commitments. I strive to live in Level 4 but I rarely do. Once you read the essay, I’m so curious to know: is level 4 somewhere you want to be? If not, why not? Where do you tend to live? Where do you wish to be?

Here’s a diagnostic to place yourself in a level: consider your response to the phrase, “There but for the grace of God go I.” Think about someone going through a hard time — poverty, incarceration, addiction, mental illness, relational breakdown — and test out how it feels to say, “There but for the grace of God go I” about their situation. If your initial response is to bristle at the suggestion that you could ever, would ever, you’re at level 1, judgment. In a judgment mindset, we think we can size someone up and condemn them or write them off. To paraphrase Jeff Foxworthy, if you say things like, “Well, that’s what people get when they’re stupid enough to ___________” or “What kind of an idiot can’t figure out not to ___________” or even, “Well, that’s (member of a certain group) for you,” you might be in level one. Judgment says, “I’ve got it all figured out. Let me tell you how you’re screwing up.” This level implies a static posture towards the person we’re assessing: judgement made, moving on.

Level 2 means to observe the same circumstance but to be able to sincerely say — almost as a prayer of gratitude like when that slip on a spot of black ice doesn’t result in a crash — “There but for the grace of God go I.” Because that reaction is really everything, isn’t it? Humility, compassion, gratitude — so much of what makes someone a person I’d like to know and, more importantly, to learn from.

By the way, how do we feel about the word “humility”? Is it too old-fashioned? Vaguely church-y in a way that just is a turn off? Too much Booker T and not enough W.E.B.? A more modern way to say it might be that someone who is humble is someone who recognizes their own privilege. They understand it would be delulu, in the parlance of our times2, to pretend they’ve avoided tragedy simply through their own wit and wisdom. Humility is viewing our assets and accomplishments as gifts rather than trophies. Humility is to say, like Isaac Newton, that if we have seen further than others, “it is by standing on the shoulder of giants.” Humility is to agree with Diogenes that “blushing is the color of virtue.” Again, to put it in modern terms: it’s having the damn sense to not get high on your own supply.

Level 3 is humility + empathy. Humility allows us to admit that it’s our privilege — and not our merit — that has kept us out of prison, off the streets and on the wagon. Empathy compels us to want to understand people who weren’t so lucky. The masterpiece of empathy-building is Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead. In the novel, Kingsolver takes the reader step-by-step along Demon’s path into opioid addiction, poverty, and isolation. Starting from Demon’s birth to an impoverished single mother in Appalachia, it’s obvious to the reader that Demon’s choices in life were few, none of them good. Kingsolver puts it this way: “A ten-year-old getting high on pills. Foolish children. This is what we’re meant to say: Look at their choices, leading to a life of ruin. But lives are getting lived right now, this hour, down in the dirty cracks between the toothbrushed nighty-nights and the full grocery carts, where those words don’t pertain.” Read Demon Copperhead and then read of the Wikipedia entry of some lucky soul like, let’s say, Ben Platt, and try “There but for the grace of God go I” on for size again.

When we are in Level 3, we look at people different from ourselves, the ones whose choices we don’t like, and we say, “Help me understand what it’s like to be you. I want to find ways to make your choices make sense to me from your point of view.” It’s a conscious choice to humanize.

Level 4 demands the most from us. Level 4 transform empathy into solidarity. Solidarity is the choice to identify oneself with those who need more and have less to give.

Are you familiar with early 20th century politician Eugene Debs?3 He was a five-time candidate for president for the Socialist Party. Although he attracted a fair amount of popular support, he never really came close to the presidency. Picture a Bernie Sanders type. In 1918, Debs was sentenced to 10 years in prison for the crime of sedition.4 At his sentencing hearing, Debs made a speech which included a memorably eloquent statement expressing the very essence of solidarity: “Your honor, years ago I recognized my kinship with all living beings, and I made up my mind that I was not one bit better than the meanest on earth. I said then, and I say now, that while there is a lower class, I am in it, and while there is a criminal element, I am of it, and while there is a soul in prison, I am not free.”

Debs is asserting that there is no act or circumstance that can break the essential connectedness of our shared humanity. Debs stands with Demon. Empathy may lead me to look on others with compassionate benevolence5, solidarity pushes me to hook my wagon to theirs so that our fortunes are linked. I tend to live in levels 2 and 3; I strive to every now and then break into level 4.

Translating again into 21st century jargon: Level 4 is the ally level. Instead of just “thoughts and prayers,” it’s a conscious choice to say that “Things will only be as good for me as they are bad for you.” I can’t emphasize enough: I don’t live like this. I wish I did. This, to me, is the height of care for another human being: to voluntarily sacrifice ones own well-being to increase theirs.

So how does this apply to my kids’ birth parents?

I love my kids so much. There’s nothing special about that. It’s just the way you love your kids too. Because of how much I love them and because of how society tends to see foster kids, I feel like I have to advocate for them and repeatedly assert their innate worth and infinite value to fight back against the stereotypes. Out of love and protectiveness for my kids, I have sometimes found myself judging my kids’ birth parents. Sometimes I’m angry at them and the way their choices affected my kids.

But when I think about it for a minute: all three of my kids are the second-generation of their family to be in foster care. That means their parents’ road was hard too. I can have empathy for that. I hope I’m interrupting that family legacy but I can still have empathy. If my kids’ birth parents were instead kids that I had adopted, I wouldn’t be looking at them with judgment, I would be dwelling on their innate worth and infinite value. I would have empathy. So it follows: if I would have done that for them as kids, they’re equally deserving now.

My kids’ parents have innate worth and infinite value. If it’s good not to judge them and it’s good to be humble and not pat myself on the back because of the privileges I’ve enjoyed and it’s good to try to understand them with true curiosity and openness., it would be infinitely better to stand with them in solidarity. Maybe someday I’ll be able to say, “While there are parents whose kids are taken away, I am among them, and while there are parents whose lives are reduced to sensationalistic headlines and statistics, I am one, and while there is a mother anywhere whose babies live in another woman’s arms, my family is not whole.”

Timely, no?

Love a Maude Lebowski moment

Which is another way of asking, “Have you read the works of Kurt Vonnegut?” I hope you have. If you haven’t, your nearest public library awaits.

He had been making speeches against World War I, against President Wilson and against the draft. Whoopsies.

Some real “be warm and be fed” energy

🙌🙌